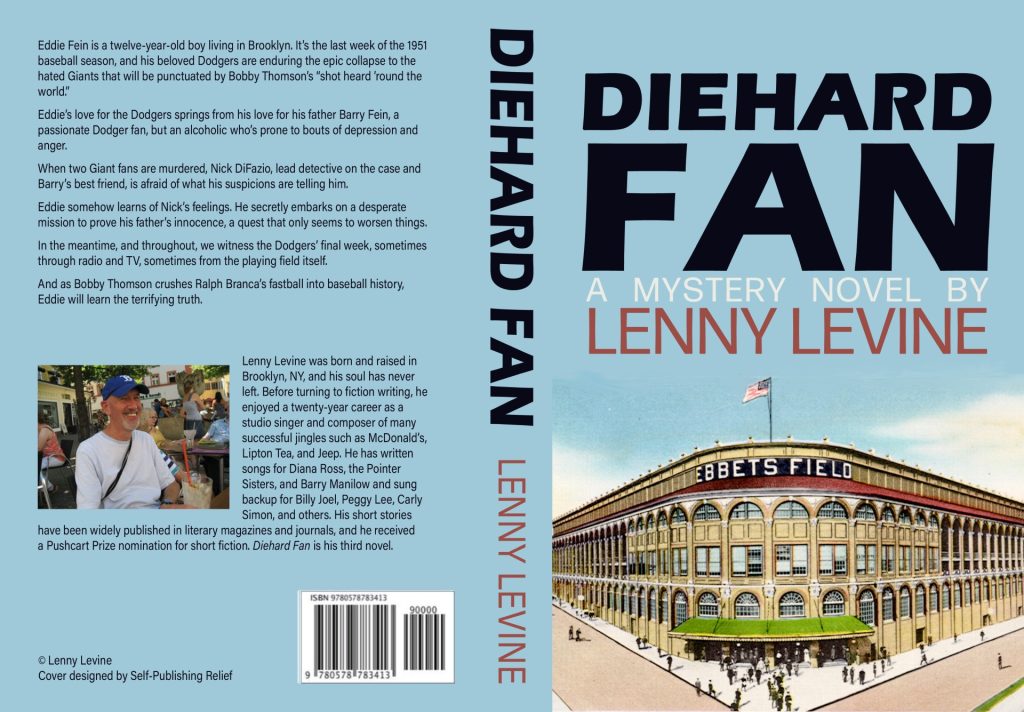

Diehard Fan, Chapter One

“Some things can affect you so disproportionately, it makes you wonder. When Bobby Thomson hit the home run, I was driving back from the Catskills with my friend Roger Goldstein, who was a rabid Giant fan. Russ Hodges’ voice was coming out of the radio, yelling, ‘The Giants win the pennant! The Giants win the pennant!’ and Roger was pounding on the dashboard, whooping and hollering and laughing hysterically. In that moment, I had a powerful urge to stomp down on the accelerator as hard as I could, run the car off the road, and smash into a tree. Can you imagine? I was actually willing to die, as long as I could take him with me.”

—My father, a Dodger fan, recalling the October 3, 1951 “shot heard ’round the world.”

Tuesday, September 25, 1951

The mist drifted out of the Boston night onto ancient Braves Field, wisps of it swirling like yellow cotton candy in the glare of the light towers. It settled on the grass and seeped into the heavy gray flannel uniforms of the Brooklyn Dodgers as they stood in the field, mixing with their sweat.

At shortstop, Pee Wee Reese kicked the infield dirt in disgust and then smoothed out the divot. With their luck, the next ground ball would have found it; that’s how things had been going. And to confirm it, he took a peek at the scoreboard. The Giants had taken a 3-0 lead in Philly.

Earlier in the inning, Pee Wee had done what he hadn’t done in a thousand chances. He’d booted a routine ground ball, and without the help of a divot. It had been the wet grass and Buddy Kerr, the Boston base runner, flashing by him at exactly the wrong moment. What else was new? He set himself and looked in to see what pitch Campy was about to call.

Carl Erskine stood on the mound and stared in at Roy Campanella for that same sign. Three runs had already scored, there was still only one out, and the bases were loaded.

In the radio booth, Red Barber was telling his listeners, “Friends, it’s only the second inning here in Boston, but we are already at the crossroads.”

It wasn’t like the Dodgers had been playing badly. Since August 11th, when they had a thirteen-and-a-half-game lead, they hadn’t been world beaters, but they weren’t beating themselves either.

It was the Giants. They never seemed to lose. The Dodgers would split a doubleheader, and the Giants would win one. If the Dodgers took two out of three in a series, the Giants won all three in theirs. They’d been slowly gaining on them for the last six weeks, and now, as Erskine stood on the mound with the bases full around him, the Giants were only two games behind.

Left-hand-hitting Braves first baseman Earl Torgeson settled into his stance and pumped his bat.

“One out,” Red Barber reminded his listeners, “and the bases are F.O.B. That’s ‘full of Bostons’ this time, folks, not ‘full of Brooklyns.’ If the Dodgers are going to stop the bleeding, it has to be now. They’ve already lost the first game of the doubleheader, and if this one gets away, and the Giants’ score in Philly holds up, their lead will be down to one wafer-thin game. Who’da thunk it?”

Erskine had to be careful with Torgeson, who liked ’em down and in. Fastball away, said Campy’s sign. Carl nodded his agreement and delivered a called strike on the outside corner.

At second base, Jackie Robinson tried to ignore the pain in his chest from the pitch that hit him in the first inning. He pounded his glove and picked up the next sign, curve down and in. That was where Torgeson liked it, but it would be out of the strike zone, and if he made contact he’d hit a ground ball to the right side. Jackie got ready to move to his left if it happened.

Erskine’s arm came around in its familiar, over-the-top motion and almost delivered a wild pitch. It bounced in the dirt at Torgeson’s feet, caroming off Campy’s chest protector as he slid in front of it and blocked it.

“Okay! Okay!” Campy called out, clutching the ball, his eyes roaming the diamond, making sure the runners stayed put. “That’s what I’m here for.”

Jocko Conlon, the home plate umpire, muttered, “Nice stop,” as he took the scuffed ball and handed him a new one.

Campy settled into his crouch again and called for the same pitch. Erskine made it perfect this time, but Torgeson didn’t bite. He let it go by for ball two.

Charlie Dressen, the Dodgers’ manager, paced the dugout, looking more like a bantam rooster bobbing back and forth than a tiger stalking up and down. He’d once told his team, “Just hold ’em close, boys; I’ll think of something.” It was funny then, but the jokes had been few and far between lately. A scant two weeks ago, he was making plans to rest his pitching staff for the World Series. Now, the only pitchers he’d rest were the ones he didn’t trust, which was everyone except his big three: Newcombe, Erskine, and Roe. They’d be doing it all from here on. Newk was pitching tomorrow and then again on Saturday with only two days’ rest in between. Carl Erskine, no matter how many pitches he had to throw tonight, would be working again on Friday. Like a jockey in the stretch, Charlie was going to the whip.

“Two-and-one, the count on Torgeson,” Red Barber reported. “Runners taking their leads, Kerr on third, Wilson on second, and the speedy Sam Jethroe on first. Erskine winds and delivers…”

A fastball meant for the outside corner, but right over the heart of the plate. Torgeson swung.

“Foul straight back,” said Red Barber as the ball clanged off the facing just below him. “You know, fans, people get excited about long, foul home runs, but it’s the fouls straight back that scare pitchers the most. Torgeson was right on that pitch and missed hitting it on the button by a fraction of an inch.”

Next came a curveball, just missing outside. Now it was three-and-two.

Barber wondered if Boston manager Tommy Holmes would have the runners moving on the next pitch. “With one out he’d be taking a chance, but his Braves are in fourth place with nothing to lose, and they can be the spoilers. Sam Jethroe, the runner on first, is one of the fastest men in baseball. Let’s see if they try it.”

Campy called for another fastball, up and in. With two strikes, Torgeson could go for it and miss, or pop it up.

“Erskine into his motion,” said Red Barber, “and there go the runners. The pitch is swung on…”

***

The borough of Brooklyn in 1951 was home to two million people and one million radios. Road games were not televised back then, so most of those radios, if they were on, were tuned to WMGM and this game. One in particular, a 1939 Philco tabletop model, sat on the kitchen counter of an apartment on Bay Parkway in the Bensonhurst section.

Eddie Fein stared across the table at it as if, by looking hard enough, he could see the players right through the maroon cloth that covered the speaker. His seventh-grade social studies report on the Incas, which he was supposed to be writing, sat in front of him, as far from his mind as Peru.

(“You know, fans, people get excited about long, foul home runs, but it’s the fouls straight back that scare pitchers the most.”)

“C’mon, Carl,” he said, with all the heartfelt urgency of a prayer. “Strike this guy out.”

Barry Fein sat across the table from his son, grim-faced, his hands clenching and unclenching in his lap. A bottle of Schaefer beer stood on the table in front of him, a pile of empties in the sink. He’d been working on the beers since they’d started listening to the game. Scotch was before dinner, and sometimes during, but ball games were for beer.

Sounds drifted in from the TV set in the living room, The Milton Berle Show. (“We have a celebrity in the audience tonight, folks, Monty Woolley. What? He’s not? Oh, sorry, madam, your beard fooled me.”) Laughter from the TV and from Eddie’s mother.

“Jesus.” Barry threw a disgusted glance toward the living room and turned up the radio.

“C’mon, Carl,” Eddie repeated, hoping that if he said it again, it might help.

(“Sam Jethroe, the runner on first, is one of the fastest men in baseball. Let’s see if they try it…”)

Julia Fein, sitting in the living room, heard Red Barber’s voice get louder and thought for the umpteenth time how her husband was almost as much of a child as her son. She looked back at Milton Berle.

(“Please give a big hand, ladies and gentlemen, to Allen Roth and his United Nations orchestra. Someday, they may all get together.”) Julia smiled and the studio audience laughed.

Eddie looked over at his father, about to ask him if he thought Sam Jethroe was faster than Jackie Robinson, but the look in Barry’s eyes stopped him. It was the kind of look he’d had the time Eddie and his friend Lionel accidentally smashed someone’s windshield while throwing a baseball around in the middle of Bay 29th Street.

“Let’s go, Carl,” he said, changing it to “let’s go.” Maybe that would work better than “c’mon,” which sounded a little whiny.

(“Erskine into his motion, and there go the runners. The pitch is swung on and lined into the gap in right-center field…”) Eddie held his breath as Barry muttered, “Shit!” (“…It’s a base hit. Kerr scores, Wilson scores. Here comes Jethroe, he’ll score…and now the throw from Furillo sails over the head of the cutoff man, and Torgeson pulls into second. Ohh, doctor!”)

“Goddamn it!”

Barry slammed his fist down on the table. The bottle teetered for a precarious instant and then fell over, spilling a stream of beer onto Eddie’s report.

“Goddamn it!” Barry said louder, swiping at the overturned bottle with one big hand and sending it flying across the room and against the wall, where it shattered.

(“Our special guest tonight is that fine British actor Nasal Bathroom, I mean Basil Rathbone,”) said Milton Berle as Julia leaped to her feet. She rushed to the living room door and stared into the kitchen in disbelief.

“What the hell is going on in here?”

Eddie held the soggy Inca report in the air as it dripped onto the table, and stared at her helplessly.

“It’s okay!” Barry said, glaring at her. “I’ll clean it up. Don’t start.”

“Don’t start? Who has to start?” she said, her voice rising. “You’re already well into it. What’s the matter, they’re losing?”

“I said I’d clean it up!”

“Are you also going to rewrite his report?” She gave an angry glance at Eddie.

“It’s okay, Mom…”

“No, it’s not okay!” Her voice had that tone that always turned his guts to mush. “You weren’t even supposed to be listening to the goddamn game until you finished your report. Did you finish it?”

“Yeah,” Eddie lied, “but it got wet. So I just have to recopy it.”

“Let me see it,” Julia demanded.

“Aw, Mom…”

“Let me see it.”

“Leave him alone!” said Barry, his eyes glinting. “I’m the one you’re after. Pick on me.”

Red Barber continued to speak from the radio as Eddie watched them stare each other down like gunfighters. Even while telling you the Dodgers were losing, the Ol’ Redhead sounded warm and soothing to him, especially compared to the angry silence flashing between his parents.

Barry unlocked his eyes and looked over at him.

“Go to your room and recopy your paper. Then go to bed.”

“But, Dad…”

“Go to your room,” Julia told him. “And dry off that report first so it doesn’t drip beer all over your floor.”

(“I saw the Sugar Ray Robinson-Randy Turpin fight,” Milton Berle was saying in the living room. “Do you know why they call him Sugar? Because when he stepped into the ring, he asked Turpin, ‘One lump or two?’”)

Eddie mopped his report with a dish towel, then headed down the hall toward his room. Red Barber’s voice was cut off in mid-word behind him. He was sure his father did it, because his mother wouldn’t dare.

He closed the door, plopped down at his desk, and stared at the wall. He hated this.

Muffled, angry voices came from the kitchen.

“…you really scare me when you get this way.” That was his mother. There was a loud bang that made Eddie jump. His father must have smashed his fist down on the table again.

His mother said something else, and then something about “your dead-end job.” There was another loud bang, and the front door slammed.

Then it was silent.

He took out his notebook and started copying his three sentences about the Incas, but he couldn’t stand it. He opened the door and looked out.

The kitchen was deserted, beer bottles still in the sink, broken glass on the floor. The door to the living room was open, and the TV was still on.

He carefully crossed the kitchen and looked in.

His mother sat on the couch in the dark, staring coldly at the screen. On it, Sid Stone, the Texaco pitchman for The Milton Berle Show, was standing behind a little table, selling Havoline motor oil. In one hand, he was holding a can of it, and with the other, he was trying to get rid of a diminutive young man in knickers.

(“Go away from me, kid, ya bother me.”)

“Where’s Dad?” said Eddie.

“Don’t ask me.” Julia’s eyes never left the screen. “And don’t ask me who he is, either.”

***

(“…Torgeson pulls into second. Ohh, doctor!”)

In the dining room of an apartment two blocks from the Feins’, Sandra Weinstock smiled delightedly.

“Ohh, boy!” she said as she softly applauded the radio. Moments before, she’d heard Russ Hodges, doing the Giants-Phillies game on WMCA, describe Alvin Dark’s solo shot, putting the Giants up 3-0. The inning had ended, and during the commercials she was switching to the Dodgers game. It had been her unbelievably good fortune to get there just in time for Torgeson’s base hit.

“Six-nothing!” she said to herself, unable to contain her joy. “They’re losing six-nothing!”

Then, as at similar times these past weeks, she thought about how her dad would’ve loved this. She looked over at her mother’s china cabinet, to a photo from ten years ago of a teenage Sandra and an overweight, balding man in a dark suit, both of them grinning like fools in front of their apartment building in Manhattan’s Washington Heights, both of them in their Giants caps.

(“Our special guest tonight is that fine British actor Nasal Bathroom, I mean Basil Rathbone.”) In the living room, Yetta Weinstock laughed, “haw, haw, haw,” in that braying sound that always set Sandra’s teeth on edge.

It was a mistake to come and live here. Even the good things happening in the game couldn’t keep that thought away. After her dad died, it seemed like the natural thing to do. Her mother needed her, and she had no particular ties to her bookkeeping job or her small apartment in the Village. No boyfriends either, for that matter.

And it was okay at first. Her mother’s apartment was large and airy, with a view of Bensonhurst Park across the street and, in winter through the trees, Gravesend Bay. She’d quickly found a job at Faber’s Sporting Goods on 86th Street under the el, keeping the books for old Mr. Faber and helping him deal with the customers.

But it was three years now, and her life was slipping away. She missed the vibrancy of Manhattan, the theaters, art galleries, and coffeehouses only minutes from her door. And her mother, let’s face it, was a first-class pain in the rear.

“You’re still listening to that game? What’s the matter with you? You’re missing a very funny show.”

She stood in the doorway, a vision of uncombed gray hair, pouchy cheeks, and stained housecoat. A cigarette dangled from her lips. Her voice had gotten deeper over the past few years from smoking, and salesmen on the phone sometimes thought she was a man.

“I’m doing fine, Ma,” Sandra said. “The Giants are winning, and the Dodgers are losing a doubleheader.”

“Big deal, there’s lots of baseball games,” said her mother. “Milton Berle is only on once a week.”

(“…‘One lump or two?’”)

She looked back into the living room, then at Sandra.

“Listen, you’re making me miss it. Do you wanna come in and watch it or not?”

“I’ve got the game on, Ma,” Sandra said, stifling a cough.

Yetta Weinstock gave her daughter one of those “what can I do with you?” looks. “Suit yourself,” she said, and went back into the living room.

Sandra turned her attention to the radio just as Red Barber was calling Willard Marshall’s base hit, scoring Torgeson.

“Seven-nothing!” she said to herself in wonder. “This is so great.”

A cool breeze drifted in through the dining-room window at that moment, bringing with it the smell of the leaves, and she suddenly needed to be outside. She wanted to enjoy this moment, and her mother’s apartment wasn’t the place to enjoy anything. In fact, she’d made up her mind; she was going to move out.

But right now she had to get into the air, away from here even for a little while. The games were going well, and she could leave them that way for now. She’d take a short walk through the park, maybe go down to the bay. She wouldn’t be gone long, and she could check in on the scores when she got back.

“Ma, I’m going out for a while,” she called toward the living room.

“You shouldn’t go out with that pneumonia of yours,” her mother’s voice called back.

“It’s not pneumonia, Ma, it’s bronchitis.”

Yetta appeared again in the doorway. “Weren’t you told it could turn into pneumonia?”

Sandra looked heavenward for a moment and tried to be calm.

“If it’s okay for me to go to work, it’s certainly okay for me to take a little walk,” she said. “Now, stop worrying.”

“Whatever you want,” muttered Mrs. Weinstock as she turned and went back into the living room. On the screen, Metropolitan Opera star Patrice Munsel was singing an aria, and Milton Berle, wearing a wig and an evening gown, was sneaking up behind her.

***

The tall, heavyset man strode down Bay Parkway toward Bensonhurst Park, his headache pounding even harder than his feet against the pavement. There was no denying it; his life was complete and utter shit.

The woman he’d married, the woman he’d once been stupid enough to love, was an ugly, abrasive bitch, whose only joy in life was to make him miserable. Day after day, without letup.

It was hard enough most of the time, but it was really hard if the Dodgers were losing, and she knew that. She saved herself especially for those times. He didn’t know what would have happened tonight if he didn’t get out of there.

He thought of the Dodgers again, because they always seemed to be on his mind. In a way, they were all he had left. The only thing in the world he could summon up any passion for.

How pathetic he was.

And even more pathetic, loving the Dodgers was like loving a beautiful woman who gets you all excited, brings you almost to orgasm, then spits in your face.

They’d done it to him so many times, he’d lost count. But this time…this time, they were doing it to him royally. They were blowing the biggest lead any team had ever blown, and it wasn’t to the Cardinals or the Phillies.

It was to the fucking Giants! The fucking Giants!

His headache flared and it made him wince. He increased his pace, pounding even harder as he strode past the park and into the underpass beneath the Belt Parkway.

The sounds of the cars above him echoed down the walls. At one point, a truck rumbled across some metal construction plates, making a loud and unexpected boom that ricocheted off the walls around him like artillery fire.

He almost screamed.

A cry came from his throat, but he cut it off, clenching his teeth and quickening his pace, finally emerging onto the promenade along Gravesend Bay.

He made it to the rail and gripped it with both hands, staring down at the black water below, his chest heaving.

Then a woman’s voice called his name.

At first he thought it was his imagination. He looked up and saw her, a small, trim figure walking down the promenade toward him. She was smiling.

It took him a moment to realize who she was.

“Sandra,” he said, forcing a smile of his own that must have looked like a rictus. If it did, she didn’t notice.

“Is it Friday already?” she asked.

“What?”

“We weren’t supposed to see each other again until Friday.”

“Oh, right.”

God, his head was killing him.

“Isn’t it beautiful out here? And we’re the only ones smart enough to enjoy it.”

He looked around and saw that there was no one else on the promenade.

“You see? Nobody,” she pointed out. “I guess we’re the only two people who aren’t fans of Uncle Miltie.”

“Uncle Miltie?” He had no idea what she was talking about.

“You know, Mr. Television, Milton Berle. Every Tuesday night, the streets are always empty like this. Everyone’s glued to their TV sets, watching that dopey show, including my mother.”

Including his wife. He tried to keep his voice steady and get through this. “I know what you mean; I feel the same way. He makes me want to wrap up the box.”

She smiled tentatively.

“Wrap up the box? I don’t understand.”

What was he doing? First, he’d had another of those Normandy flashbacks in the underpass, and now here he was, lapsing into his private sense of humor.

It was secret little jokes to himself that got him through life as a child on the Upper West Side. It was why he rooted for the Dodgers instead of the Giants. To set himself apart from all the jerks in the neighborhood, which was everyone.

“‘Wrap up the box’ is just an expression of mine,” he explained. “It means ‘turn off the TV.’”

It took her a moment, and then she laughed.

“Very clever.” She looked at him in admiration. “I think you’re actually funnier than Milton Berle.”

“Well, that’s not saying very much, is it?”

She laughed again, and he liked the sound. Was his headache starting to ease up a little? He thought so. Maybe it was good that he’d run into her.

“Wrap up the box,” she said, “can I use that? I’ll give you credit for it, I promise.”

“Be my guest.” Now he was smiling himself. “You seem to be in a good mood.”

“Do I? I guess it’s because it’s a beautiful night, the Giants are winning, and the Dodgers are losing a doubleheader.”

If she’d suddenly pulled a knife and stabbed him, it wouldn’t have been more unexpected. He stared at her.

“I’m a big Giant fan; you can probably tell,” she went on. “It’s been like a miracle!”

She interpreted his look as one of interest and gave him a mischievous grin.

“You know, I almost feel sorry for the Dodgers. Because they know my Giants are gonna catch ’em. Because they always blow it in the end.”

She laughed again. It made her look like a gargoyle. He winced, but she didn’t notice.

“It’s like a tradition with them.”

His headache was back now with a vengeance, bursting into excruciating waves of pain.

“They do it every year, like clockwork. If it’s September, you know it’s time for the Dodgers to do their September swoon. And they do, they certainly do. They fold like a cheap…”

Her voice grated like fingernails on a blackboard. His head was exploding. He had to stop her. She was killing him.

“Shut up” was what he meant to say, but instead, he found himself reaching for her.

“What are you…?” was all she could manage, and then his hands were around her throat. He pulled her toward him, her eyes wide in disbelief. To anyone passing at a distance, they might have been lovers about to kiss. But there was no one in any case.

“Shut up! Shut up! Shut up!” The words shrieked in his mind, but no sound came from his lips.

She flailed desperately in his grasp, struggling to breathe, her fingers clawing at his hands, trying to pull them away. He was oblivious to it, as he was to everything but the voice inside him, screaming, “Shut up! Shut up!” His fingers tightened around her neck.

Her right hand caught on his watch and tore it off in a spasm, clutching it like a final souvenir of her life, the life that was slowly being squeezed out of her.

Moments later, he stood gaping into her unblinking eyes, her body slumped against his. The sounds of the cars rattling the plates on the highway came from far away, and he could hear the lapping of the water below. In the distance, across the bay, the lights of the Parachute Jump in Coney Island winked red, blue, and green.

What just happened? he thought. A chill took hold of him, like an icy fist, grabbing his heart. What in God’s name just happened?

He was still holding onto her. Fearfully he looked around, but saw no one. He lifted her, carried her to the rail, and lowered her over the side, hearing the splash as she fell into the bay.

He was shaking, but, incredibly, the pain in his head was diminishing. On wobbly legs, the man began to walk back down the promenade toward Bay Parkway.

He gritted his teeth through the underpass and was just past the park and starting to get himself together when a new kind of panic hit him. His Hamilton watch was gone.

Was it on the promenade? Should he go back and look? No, too risky, and besides, he probably left it at home. At least he’d better have.

But he had to wait. He couldn’t go home yet, not until he was sure his wife was asleep.

His mind in turmoil, the tall, heavyset man kept walking.